Selling

“Google will almost certainly flame out as a business. I’d wager that odds are at least 90% that its profit margins and growth rate will be materially lower five years from now. I believe that it is virtually certain that Google’s stock will be highly disappointing to investors foolish enough to participate in its overhyped offering — you can hold me to that.” – Tilson, Motley Fool, 2004

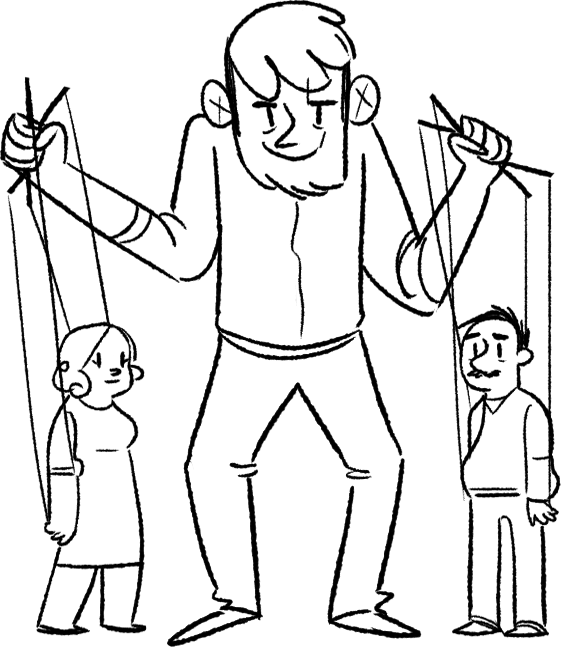

Everything I know about sales and selling I learned from my father.

By 1987, I was tearing my hair out, and I felt I had to move on from my job in a hospital. During the previous twelve months, a few pharmaceutical companies contacted me about switching to a career in pharmaceutical sales. I turned them all down simply because I had allowed my mentality to form a negative image of what it meant to be a salesperson.

George was my grandfather and Harry was my father. They had been salesmen most of their lives. I formed an opinion on sales and selling based on their attitudes and behavior.

When Harry ran a tire depot, I took my vehicle in for one replacement tire. One of his partners inspected the car and assured me I needed four new tires instead. Having no clue myself and thinking my own dad would have my back, I went along with it. After the job was completed, and I had paid in cash, I overheard the two joking that they had just talked some sucker into buying four new tires he didn’t need. My father looked outside to see who the sucker was. When he saw me, he slunk back to the safety of his desk without another word. That was his style. Whatever he could get away with was a triumph to him, no matter who was the victim. I also bought auto insurance from him only to discover after a traffic accident years later, and a subsequent court summons, that he used my cash for other things.

He sold mortgages to people who really could not afford them. He was only interested in making commissions and did not care what happened to his customers after that. Having never had a mortgage himself, he lied to them about his experience and most fell for it. Those observations had my neurons wired with a negative impression of the character required to be in sales.

At the same time, my wife was feeling a bit burned out after twelve years working on a cancer ward. She needed a break and, at the very least, a vacation, but our combined salaries barely covered the mortgage, and we had too much debt. Finances were tight and we lived on convenience food of the “just add water” variety. We were in financial quicksand. One of my dreams was to travel and experience other cultures and companies, and somehow that was not happening. I needed a rethink.

After taking quiet time one day, I somehow decided that I would take the next sales job offer that came along, and do it for only a couple of years until we recovered financially. That seemed like a good idea, and a compromise that could get me over my hang-up about salespeople. That might not sound like a moment of brilliance, but at the time it felt like it. If I could survive the military, I figured I could be a salesman for a couple of years. We would get back on our feet and also have some money for a vacation or two.

Not having a vehicle at that time, I cycled to one of my favorite scenic spots, a pond in the center of a village green. Once there, I went through a commitment to change ritual, exactly as outlined in this Step Two. Whenever a good idea comes to me, I do this exercise and write out a new statement that fixes the new idea in my mind. The formality of this commitment always seems to trigger an increase in small daily miracles.

Within a week, I had received several unsolicited phone calls about potential sales jobs. I was then invited to interview with the UK division of a large French pharmaceutical company that was expanding its sales force. There was a vacancy right where I lived, and the salary plus benefits were enough to double our household income. The phone call came out of the blue, as a result of someone at the hospital recommending me to a sales manager they had met months earlier.

Family and friends warned me against taking the job. They said I had a secure position at the hospital and that in sales, people were let go all the time. They told me I was not cold and calculating enough in that dog-eat-dog world. Their fear for me was out of a genuine concern for our welfare, but I still needed to filter out that energy and choose my own reaction. I chose to follow the synchronicity that had just shown up, and I accepted the offer.

I started off as a trainee sales representative, which, despite the better salary, was something of a step back from the fancy title I had at the hospital. In many ways, the hospital position had been a cliff fall below where I was in the Royal Navy. To everyone’s view I was going downhill fast, but I didn’t see it that way. I was already aware of the way of the winding staircase in my life. That did not stop the criticism or gossip all around me, and I had to work hard to tune it out.

On the five-week training course, I stuck with my Taking Quiet Time discipline, and to my surprise found that I was a natural. Ideas, answers, and solutions all popped into my head when I needed them. More surprising was the fact that I found myself thoroughly enjoying the experience. The high integrity of my peers and bosses surprised me and completely changed my mental image of what a successful sales person is all about. These people really cared about the patients as much as their own success, and most had a medical background.

When I was let loose on my sales territory, I found that the customers I called on liked the fact I had experience of the hospital life, and appreciated that I knew the limitations of our drugs as much as the benefits. I discovered sales was not about “taking,” as my father seemed to think, but about “giving,” by satisfying customers and their needs.

I never looked back. I woke up every morning excited to go to work. Six months later, I was sunbathing in Spain after winning my first sales prize. Within a year I was in Nassau for a week, and the following year, I learned to ski in Switzerland. Travel was back on the agenda.

Within a few months, I was promoted to professional sales representative, and then to executive representative by the end of the first year. Taking quiet time was easier now because I had a company car. If it was too noisy at home, I would drive a half-mile to a quiet spot and find stillness for twenty minutes before driving on to my first sales call.

My regional manager was easy to work with, but he had been in the job many years, and he was counting his days to retirement. Great ideas for improving efficiency and success kept popping into my head, and unlike the hospital staff, he was receptive to it all, so long as I did the work to implement them. He came to rely on me to take any new recruits under my wing, and for the general organization of the region. I was promoted once more, to district manager.

At the end of 1988, less than eighteen months since I made the commitment to change, I was promoted a fourth time to regional manager in charge of a team of seven salespeople, all older than me. Next, I found I was being head-hunted by a progressive company, and I was able to instigate more bright ideas to improve our success as a team. At that company, a global conglomerate, I won manager of the year three years running. I enjoyed the recognition, but more than that, each prize came with an extra week’s vacation and $4000 in travel vouchers. My wife and I had some of our best travel adventures ever.

Then in 1991, I was the first sales manager ever to win the UK marketing professional of the year. The people in the marketing department were furious about the award, but their fury was born of embarrassment that none of them had even been nominated. Reluctantly, they attended a big awards ceremony in London when, with my mentality shield firmly in place, the corporate president presented me my prize on stage. There was a bronze statue and a sealed envelope. Given the multi-billion dollar profits made by the corporation, I felt sure that envelope held my financial freedom. In the privacy of a restroom cubicle, I nervously tore open the envelope and then stared in disbelief at my prize—a single share of stock (worth about $90). Rare is the person who gets rich working for someone else!

I introduced my early version of Three Simple Steps to the sales forces and watched with pride over the next years as many went on to enjoy similar success. In my experience of sharing this philosophy, I found most people readily accepted Steps One and Three but struggled with Step Two. It seemed possible to have some success by implementing part of the program, but I wonder how far they might have gone if they could have got over their discomfort at something as innocuous as taking quiet time for twenty minutes a day.

I introduced my early version of Three Simple Steps to the sales forces and watched with pride over the next years as many went on to enjoy similar success. In my experience of sharing this philosophy, I found most people readily accepted Steps One and Three but struggled with Step Two.

It seemed possible to have some success by implementing part of the program, but I wonder how far they might have gone if they could have got over their discomfort at something as innocuous as taking quiet time for twenty minutes a day.

Success continued for me after moving to the United States in 1994; before long, I was enjoying the high life with a mid-six-figure salary, a job I enjoyed, and the sort of travel and adventure my wife and I had dreamed of in our courting days. Since seeing that look in Harry’s eyes in 1983, I had done nothing more profound than add Step Two and Three to my life. The changes in my life were incredible. I had not acquired any new skill or talent or won the lottery, but people we knew thought I must have.

After seeing Harry in that state of near-homelessness, my siblings and I rallied for a few years to help rebuild his life and self-esteem, each doing their bit to try to keep the pretense of family unity. He found work as a taxi driver. Soon, he met a female passenger who had recently lost her husband to cancer. They bonded. She needed someone to care for, and he needed to be taken care of. He moved into her neat cottage and lived a normal life again with good food, clean clothes, and an endless supply of cigarettes.

Harry continued with his shady dealings, some of which required me to attend court to plead my innocence of fraud. Eventually, I had to make one of the hardest decisions of my life and switch that negative input off. Sometimes, it is the only solution, and I kept my communications with him to a minimum from then on.

His lifelong smoking finally caught up with him when he was diagnosed with esophageal cancer in 1995. He was admitted to hospital for surgery. I flew over from the United States. My sister was at his bedside and looked concerned when I walked onto the ward. She knew there was tension between us, but I simply kissed him on the forehead, and he greeted me with the same, “Hello, Son,” as when I encountered him in that hovel, and as if he had been expecting me all along.

He died in 1996. Three people attended his funeral: his girlfriend, his aunt, and one of his children. He is buried next to Audrey.

At the only funeral home in the nearest small town, my siblings were taking care of duties when the director said that he recognized the family name, and started turning pages in a dusty ledger. “I believe I arranged the burials for his father and mother many years ago,” he said while scanning lists of the names of the deceased. He stopped on a page. “Ah, yes, here they are. George Frederick, 1971. Emily, 1976.” He paused, peered over his spectacles, and made an embarrassed cough. “I’m afraid your father never paid for any of the funerals.” It was fitting irony, and my siblings said they tried not to laugh as they handed over a credit card.

I learned much about the mentality it takes to succeed in a virtual business from observing my father. He started and failed in business many times. We were poor and lived on welfare, which is not the ideal environment to start businesses given that it was an illegal practice while drawing welfare checks. I always felt, however, his attempts were doomed from the outset by his mentality. He was a man who only cared about what was in it for him. The reason he started each business was because he saw potential for personal gain, an edge, a way to get one over on the customer or competition.

What is wrong with that, I hear you ask? Well, in my opinion everything.

What sales really is about

If you search online, you’ll read gobbledygook like this: Sales skills are the competencies a rep should have to successfully sell a product/service. It includes skills like prospecting, knowledge of sales tools, etc, and communication skills like persuasion, negotiation, etc.

Since when was trying to convince a person against their will a positive trait?

Negotiations are not sales skills.

They are negotiating skills.

There is a huge difference.

Should not knowing your customer’s needs be more important than knowledge of sales tools?

The successful sales mentality is not about gain, but service. It cares more about satisfying the customer’s needs than those of the sales professional. The first thing you must think of when you rise, and the last thing before you sleep is, “what is in it for my customer?” “How do they benefit from my efforts?” Your mentality must be focused on how you can serve, and then how you can serve well, and then how you can serve better. I call it the, “benefit mentality.”

I have a friend who is trying to get a business off the ground. She has a new line of products, and has convinced herself that the secret to success with the venture is all about having an eye-catching label on the bottles. She sees the venture as a way to make a mint. She is obsessed with the brand, and not the customers. She is in love with the bright pink label because she likes bright pink. I have asked her a dozen times to explain to me what benefit her product would provide for a potential customer. She says, “Look at the label. Isn’t it a great color?” I nod my head and say “Sure, it is a nice feature, but what does it do for the customer?” “It’s bright pink,” she repeats as if that means anything at all.

Her business is going nowhere because she simply does not understand the difference between features and benefits.

A feature is a fact about a product or service that, by itself, offers no one a solution or satisfaction. It may be interesting, but usually not compelling to make us do something… like buy it. A benefit is what the feature means to the customer in satisfying a need they have. They buy it for the benefit it could give them not for the pretty label.

A pretty pink label is a feature that offers the customer no benefit whatsoever. A benefit could be that the product is allergy free, which means that anyone can use it safely, or that it rinses out easily which means that customers save on water costs and shower time or that it is more cost effective and lasts longer than competing products.

The secret to understanding the difference between a feature and a benefit is to constantly ask yourself “So what?” Follow every statement with the words “which means that.” If you cannot complete the sentence then you have a feature rather than a benefit. It is only by creating benefits that we satisfy customers, and only by having happy customers can be have a robust business. So many businesses lose money by advertising features.

If you have the mentality of “What is the benefit for my customer?,” you will create in yourself a selling mentality rather than the self-serving mentality that most companies who focus on features have.