Survival = Access To Funds (as needed)

“…Apple [is] a chaotic mess without a strategic vision and certainly no future.”

– TIME Magazine, 1996

Other than the rare diamond in the rough, a company cannot succeed without investment. By succeed I mean become one of the 1% of start-ups that make more than $500,000 a year in receipts. That statistic still stuns me. According to the US business census 96% of all non-employer companies make less than $50,000 a year in receipts, and only 4% make more. Only 0.8% make more than $500,000. Cash-flow mismanagement is probably the cause.

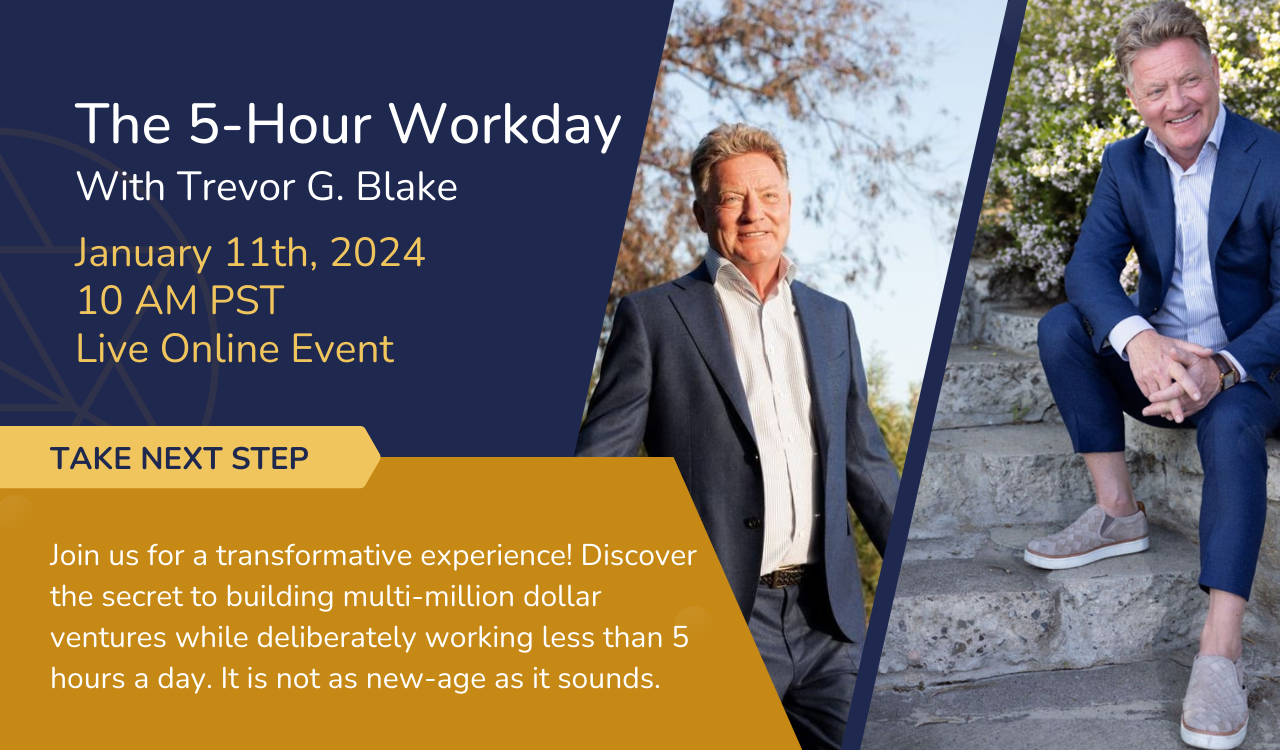

My first company made 76% NET profits on annual revenue of $15 million. Those numbers resulted in a more than seven-times multiple sale. It took five years to build it to that level. I did not hire a single employee and when it sold, I was still working from a spare bedroom converted into an office. It is possible if you start-up the right way.

From what you learned about managing cash-flow, there is good reason to think that you can succeed. One strategy you can use to avoid the cash-flow traps is to get external investment so that there is always a cash cushion, or at least to get access to a line of credit – just in case it is needed.

The worst thing you can do is postpone fund raising until a crisis hits. Investors invest in potential success not companies in the early signs of death.

You also always need access to capital to speed up growth and to provide short-term support to cover the period between production output and revenue input. Demand needs to be satisfied or it goes away quickly. Production delays due to insufficient cash can kill a company. You need to be able to scale up when necessary, which means you need access to financing.

As the leader, you also need to be mentally free to focus on growth and not stressed out about the next due rent or supplier payment. When starting a new business most entrepreneurs lack sufficient capital of their own to survive long enough to get through the challenging cash-flow period.

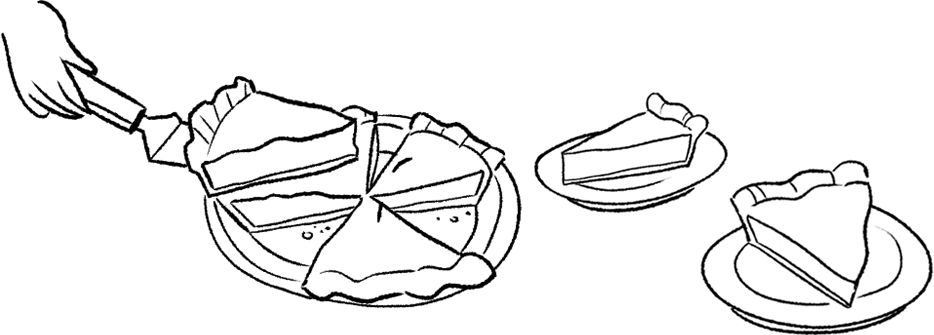

Investment comes at a price, which is usually a slice of your company pie. Many first-time entrepreneurs are reluctant to give up a share of ownership in exchange for the money that can aid his or her survival. But why would anyone invest in your company except for a piece of the pie? I am a proponent of using external cash as soon as possible because I would rather own 10% of something than 100% of nothing. A 2015 Tufts survey concluded than the average founder/CEO of companies in the U.S. owned <15% equity in his or her company. For most of you doing this course, if I told you I would invest $1 million, but your ownership is reduced from 100% to 10% you would refuse the investment. If, however, I could guarantee that the investment resulted in you being able to grow the company quickly and then sell for $100 million, of which you get $10 million you would likely take it in a heartbeat -10% of something is something. 100% of nothing is nothing. When the founder accepts investment in lieu of equity, however, they do not always anticipate the effects of that dilution over time.

First, let us discuss the sources of funds. Then we can get into the trickier subjects of valuation and dilution calculations.

Source of Funds:

In an INC 500 survey 41% of CEOs stated that they launched their businesses with $10,000 or less of their own money. More than a third of those entrepreneurs started with less than $1,000. Each year’s list looks very much like the lists of years past when it comes to the number of founders who started companies with little seed capital. That sounds like a lot of bootstrapping. Nothing wrong in that, but also keep in your mind what we discussed at the beginning of this course. The majority of companies make <$50K a year. Why bother? The good news is that there is always a plentiful supply of money. Entrepreneurs often tell me, as if it is a fact, that it is impossible to raise money in the current economic climate. They hear this in the media, or read it online, and then regurgitate it as fact. In fiscal year 2016, however, business loans for less than $1 million totalled nearly $900 billion.

It sounds like a lot of lending to me. Even as banks were being closed at an alarming rate in 2010 and 2011, the number of small business loans remained steady at a total of $700 billion. The SBA definition of a small business is one with less than 500 employees, which is a business that I don’t consider small at all. A small-business loan, however, is usually quite small indeed and usually well under $200,000. It is enough money to get started, but winning ideas usually need a lot more in the short-term. The National Federation of Independent Business reports that about 40% of the small businesses it surveys cite poor sales as their main business problem. In contrast, only 8% report that they can’t get all the credit they need. So, money is available even if it may take a lot of effort to get your hands on it.

Let’s look at the pros and cons of the various options for raising additional capital.

Using your Savings:

On TV recently I watched an “investment expert” state that an entrepreneur should only start a business when he or she has at least two year’s worth of “salary” in their savings account. I had several reactions to that piece of advice. I agree that any entrepreneur needs a cushion of cash to get through the potentially bumpy period when revenues try to catch up with expenses.

Winning ideas, however, cannot wait two years for implementation. I also question just how many people in any society are in that healthy situation of being able to rely on savings.

The average American household has $16,000 in credit card debt, and when mortgage, student loans, and other liabilities are included, the average household has up to $225,000 in debts. A survey in 2015 warns that the average non-mortgage household debt in the UK will be £10,000 by the end of 2016.

The McKinsey Global Institute in 2015 reported that Canada, Netherlands, South Korea, Sweden, Australia, Malaysia, and Thailand face a crisis as a consequence of rapid increases in household debt. Most people don’t have any savings, let alone two year’s worth.

Conversely, if you are lucky enough to have a financial safety net of two year’s worth of savings, what on earth are you waiting for? Do you really have the fire and passion necessary to build a successful business if you are forestalling for the perfect set of circumstances? If you do have such savings to rely on, then the good news is you can avoid dilution of ownership at least for a while. What are you going to live on in the meantime? It’s Texas Hold ‘em style and all in. Businesses can fail through no fault of the entrepreneur, and if it is your life savings that have been invested, it will hurt more than it should. Most people’s savings are also not their own, but their family’s. This requires 100% commitment from everyone, or it can tear relationships apart when things get bumpy.

Also, because you are the sole investor, you are now the sole source of knowledge, connections, and experience. When we start out, most entrepreneurs don’t know what it is they don’t know. That can be dangerous. There is much to be said for bringing in investors who have experiences that can help us avoid mistakes.

For me this is as important as the money they bring.

Banks:

Banks are an obvious source, but unless you approach a lender with guaranteed sales or contracts that can act as collateral, it will be unlikely anyone will take a risk without something significant in return.

The law requires banks to have collateral before they can lend. Strictly speaking, banks are not supposed to invest in businesses. They are regulated by federal laws, which exist to prevent them from taking depositors’ money and using it in a reckless manner. You would not want your bank to be investing your savings in risky ventures so why would you expect one to invest in yours. Federal regulators want banks to keep money safe, in very conservative loans, backed by solid collateral. Start-up businesses are not usually safe enough for bank regulators, and they usually don’t have enough collateral.

A business that has been around for a few years, however, can produce enough stability and assets to serve as collateral. Banks commonly make loans to small businesses backed by the business inventory. Other small business financing is accomplished through bank loans based on the business owner’s personal collateral, such as home ownership. Some would say that home equity is the greatest source of small business financing. Aside from standard bank loans, an established small business can also turn to specialists to borrow against its accounts receivables. The most common accounts receivable financing is used to support cash-flow when working capital is hung up. Interest rates and fees may be relatively high, but this is still often a good source of small business financing.

In most cases, the lender doesn’t take the risk of payment—if your customer doesn’t pay you, you have to pay the money back anyhow. These lenders will often review your debtors and choose to finance some or all of the invoices outstanding.

No matter the type of bank loan, the downside is that the loan requires regular repayments and that’s hardly helpful to cash-flow security.

Angel Investors and Venture Capital:

Angel investors are individuals with a high net worth, or groups of such individuals that collectively invest in an idea. Capital amounts are typically from several thousand to below $2million. Venture Capital is money provided by investors to start-up firms and small businesses with perceived long-term growth potential. It typically entails high risk for the investor, but has the potential for above-average returns. Venture capital can also include managerial and technical expertise as part of the package.

Most venture capital comes from a group of wealthy investors, investment banks, and other financial institutions that pool investments or partnerships. Many global, established companies also have venture capital divisions that seek out breakthrough ideas to invest in. This form of raising capital is popular among new companies or ventures with limited operating history, which cannot raise funds by issuing debt. The downside for entrepreneurs is that venture capitalists usually get a say in company decisions, in addition to a sizeable portion of the equity. I am a proponent of selling ownership for cash because with no repayment in the near term the funds do not impact cash-flow. Given the main goal is to survive long enough, if equity investment can be attracted, it gives you a much higher probability of making it.

These type of investors like to complete detailed due diligence on the new company, and that provides a thorough objective test for the merits of your winning idea. The investors bring structure and experience to a business. They often have industry or technical knowledge of your markets, as well as networks with additional lenders and potential new customers. Some also provide in-house value-added services such as accounting and tax preparation.

The Consequences of Dilution

In order to afford the first pieces of the Apple I in 1976, at a time when the US economy was plagued by inflation and unemployment, it is said that Steve Jobs invested $1,500 in proceeds from the sale of his vehicle. Steve Wozniak sold his Hewlett-Packard 65 for $250. The third founder, Ronald Gerald Wayne, was given a 10 % stake in Apple, but sold out for $800 only two weeks later.

At the request of venture capitalist Arthur Rock, and ex-Intel manager Mike Markkula, Apple was incorporated in 1977. Markkula brought his business expertise along with $250,000 ($80,000 as an equity investment in the company and $170,000 as a loan). He owned one third of the company in exchange for the cash. The investment helped Apple survive and then flourish.

When Apple went public, it generated more capital than any IPO since Ford in 1956 and instantly created 300 company millionaires. At that point, the exchange of equity for a small amount of cash seemed like a good deal to everyone involved.

Post IPO, Steve Jobs ownership had been diluted to 13.5%, Steve Wozniak’s to 7.1%. While that seems small, it is typical for business ownership. The two founders of Google own 16% of the company between them, and even Bill Gates only owns 40 % of Microsoft. EBay’s two founders have 30% and 20% ownership respectively.

Starting and surviving are two very different phases. You can start a company with nothing more than a few hundred dollars to incorporate an idea. To survive, you are going to need cash to see your idea through the period of expense-related growth before sufficient revenues start to flow. All the issues of cash-flow in the early bumpy years can go away if you can attract external funding. Get used to the idea that your percentage of ownership will be heavily diluted regardless of how much cash you need to survive.

Dilution Over the Long Term:

Imagine you come to the negotiation table with three other partners, and a great idea, and together invest a mixture of savings, credit cards and loans leveraged against your homes. The total is $2million, which means that you have committed $500,000. You negotiate with angel investors to add $500K for a post-money valuation of the company of $2.5million. The angel investment is worth 20% equity and the founders keep 80%. As one of the four partners your $500,000 share is also 20%. (before the Angel investment you owned 25%).

The company survives, grows, and then an opportunity to expand the market arrives. With the help of the angel investors, you all convince a venture capital fund that your valuation is now $10 million pre-money (you, your partners, and Angel investor are worth 20% of $10 million or $2 million each), and they VC agrees to add $5 million to the company for a post money valuation of $15 million, but in exchange for $5/15% equity or 33.33%. You now owe 20% of 67% or 13.4%, but it is worth $2,010,000. You have more working capital to grow, but your value is pretty much the same.

It is also agreed that the company needs to create a stock option pool to attract top talent to the growing company. In a typical deal, the founders and angel investors have to create that pool from their own equity shares. Each agrees to allocate 2.5% so that 12.5% ownership is allocated to the pool. That leaves the founders and Angel with 54.5% or $1,635,000 each. You had better use that working capital well.

As the company grows, it sees a need for more investment. The first venture capital round is usually called the A-Round or A-Series. The B-Round invests $8 million for a post money valuation of $23 million. The stock option pool needs to be topped up to continue to recruit top talent, and a further 6% total of everyones ownership gets added. The B-round investor owns 8/23 = 34%. 18.5% is in share pool. So the founders and investors now share (47.5%*23million/5 =$2,185,000 each which 9.5% equity each)

At exit likely they will pay long-term capital gains tax on any profit, and let’s say it took ten years to achieve an exit for which the first 2 years the founders took no salary. Let’s say the company sells for $50 million, each founder walks away with just under $5 million minus capital gains tax, minus state income tax, minus lost earnings. Maybe they clear $3 million in profits each. Overall not bad, but the example saw a company go from $2 million to $50 million and I doubt the founders feel great about the end result. It is a very realistic example. Overall $3 million and a blast of an experience is a great result for most people who left a dead-end job to start-up. A few better decisions along the way could have resulted in a higher payday.

Such as:

The more partners you bring in at the start, the bigger the dilution downstream. Many start-ups behave like a jolly-boys outing. Friends come together, share a vision and go into business together. You must think carefully about it. Is every partner absolutely necessary for the growth of the business? If not, what other ways can you find to get that starting capital? The fewer founders you have the better off you will be when you exit the company.

Time and taxes take their bites out of your success. Consider earlier exits and different tax options (like placing the company in a zero state income tax, FL, NV, WA)

The first pre-money valuation is critical. Stand your ground, and use the business-plan process to justify your valuation. Get it as high as possible without frightening the investors away.

Each round of financing adds layers of complexity that can further dilute the founders.

Resources

In this video, you will feel the excitement of our first VLS-E crowdfunding. Member, Kirsty, started Underbunks.com and eventually raised >$150,000 through this exclusive group.